Lee Miller: Fashion Icon, Muse, & Wartime Photographer

Born on April 23rd, 1907, in Poughkeepsie, New York, Lee Miller’s journey through life was nothing short of extraordinary. She became a pioneering force in the realms of modelling, surrealism art, fashion, and photojournalism. Her remarkable journey through the 20th century bore witness to transformative cultural shifts, from the glamorous heights of the fashion world to the harrowing depths of war-torn Europe. Let’s explore the intricate tapestry of Lee Miller’s life, illuminating the woman behind the lends whose artistic brilliance and resilience continue to captivate today.

Self Portrait by Lee Miller New York, 1932 © Lee Miller Archives

Miller was born Elizabeth ‘Lee’ Miller, to Theodore and Florance Miller - her father, Theodore, was of German descent whilst her mother was of Scottish and Irish descent. Lee grew up with her two brothers, Erik and Johnny, who were all introduced to the art of photography as children thanks to their father's hobby. Lee was Theodore’s favourite when it came to photography as she would often pose for his photos, and she in turn developed a keen interest in her father's hobby and became familiar with technical aspects of the art. However, her father's motives have been called into question as he often had his teenage daughter pose nude for his photos. These nude photos have been a controversial topic, as many have viewed them as sexualising an underage young woman, whilst some have argued that the pictures were taken for artistic purposes. In the 2020 documentary ‘Capturing Lee Miller’, Lee Miller’s son called the works a “transgression of a relationship”. Lee herself never left any documentation of her accounts of posing for her father’s photographs, leaving her feelings on the topic largely a mystery.

The Miller Family, 1923. From left to right: Theodore, Lee, Erik, John, and Florence

Unfortunately, at the age of seven Lee was sexually assaulted while staying with a family friend in Brooklyn and contracted gonorrhea. Historians have suggested that her assault may have made her more susceptible to the traumas she would endure later in life as a result of being a war correspondent in Europe.

Lee also had a fair amount of trouble with her education as she was expelled from almost every school she attended whilst living in the Poughkeepsie area. When she turned 18 in 1925, Lee moved to Paris and attended Ladislas Medgyes’ School of Stagecraft where she studied lighting, costume, and design before returning to New York the year after to attend the Art Students League of New York to study life drawing and painting. But it was a near-miss accident which would change the course of Lee Miller’s life, as she nearly stepped in front of a car in Manhattan but was stopped by Condé Montrose Nast, the founder of Condé Nast who published Vogue and Vanity Fair. Nast was immediately captured by Lee’s beauty, and the incident helped launch her modelling career in fashion publications, and the then editor-in-chief of Vogue thought Lee was exactly what the publication needed to represent the emerging idea of “the modern girl”. Her first appearance in Vogue was in the March 15th, 1927 issue where she appeared in a blue hat and pearls drawing by George LePape.

Lee Miller on the cover of British Vogue, March 1927. Illustration by George LePape

Lee quickly shot to the game and became one of the most sought-after models for fashion magazines, becoming the face of Vogue and collaborating with esteemed photographers including Edward Steichen and surrealist artist Man Ray. Her modelling career flourished until 1929 when it came to an abrupt end.

Lee Miller for Vogue, 1928. Photographed by Edward Steichen

Kotex, an American brand for menstrual hygiene products, featured a photograph of Lee shot by Steichen to use in their advertisement for their menstrual pads. Steichen had sold his photograph to Kotex without Lee’s consent, causing quite a stir as it was a taboo topic which mortified the American public and Lee herself. This single-handedly ended her career as a fashion model but allowed her to continue pursuing her more artistic channels in Paris - where one door closed another one opened for Lee.

Edward Steichen's photo of Miller which was sold to Kotex - making her the first woman to appear in an advert for menstrual products

Once in Paris, Lee visited surrealist artist Man Ray and insisted she take her under his wing as an apprentice. Although he firmly stated he didn’t take apprentices, she became his model, collaborator, and even his muse and lover. Lee and Man Ray worked so closely that Lee actually took some of Ray’s photographs - it became difficult to distinguish their work. During this time of her life, Lee became familiar with the editor of French Vogue, Duchess Solange d’Ayen, Pablo Picasso (who remained a lifelong friend), Paul Eluard, and Jean Cocteau. But as with most things, Lee grew restless and sought out a new venture for her artistic career.

Glass Tears,1932 photographed by Man Ray

Returning to New York in 1932, Lee opened her own photography studio, the Lee Miller Studio, and hired her brother Erik as her darkroom assistant. Lee worked with prestigious clientele including Elizabeth Arden, Helena Rubenstein, and Saks Fifth Avenue. The studio would be in operation for two years until she met and married Egyptian businessman Aziz Eloui Bet. She subsequently left her studio to enjoy life with her husband in Cairo. She didn’t work professionally as a photographer during her time in Egypt but did continue the art as a hobby, before, unsurprisingly, growing restless in Cairo and returning to Paris in 1937 where she would meet British surrealist painter Roland Penrose (her future husband despite still being married!)

The Shadow of The Great Pyramid, 1937. Copyright © Lee Miller Archives 2023

The outbreak of the Second World War became a pivotal moment in Miller’s life and was eager to return to professional photography. Her family in New York pleaded with Lee to return home to safety, but she couldn’t be swayed from her new goal.

Making the most of her contacts in the fashion world, Lee approached British Vogue offering to work as a photographer but was rejected for the role - she instead took the position of studio assistant.

As more men were conscripted into military service, the UK turned to women to help fill the jobs which men had left behind. Several male photographers for Vogue also left to join the war, and Lee began to take on Vogue’s fashion and lifestyle photography. Vogue published several photo essays captured by Lee, including her 1943 work “Night Life Now” where Lee captured the after-work life of women’s Auxiliary Territorial Service. Lee’s photography helped British Vogue to transform from a luxury-oriented fashion magazine, which at the time had found itself ill-equipped to meet the war-torn moment, into a publication for serious news.

Anna Leska, ATS pilot flying a spitfire, White Waltham, Berkshire, England 1942. Photographed by Lee Miller.© Lee Miller Archives, England 2015

The British government also understood the importance that women’s magazines played in helping their readers cope with the changes and challenges brought on by wartime shortages, clothes rationing, and women entering the workforce in large numbers. The Ministry of Information worked closely with publications such as Vogue and in turn Lee Miller to help promote their “Utility Clothing”which was created to help provide the public with quality garments at affordable prices. Lee also reported on the blitz, creating some stunning surrealist photography which captured the resilient attitude in London.

Model Elizabeth Cowell wearing a Digby Morton Suit (a design for utility clothing), photographed by Lee Miller, 1941. ©Lee Miller Archives, England 2020

In 1944, Lee progressed her photojournalism career by travelling in person to war-torn France to report for Vogue. During this time, she displayed unparalleled courage, documenting the grim realities of conflict, and capturing images that would later become emblematic of the war’s brutality.

Lee’s first port of call was in Normandy, France, just a month after D-Day to report on American Army nurses in a field hospital near Omaha beach and share their stories with the allied press. After a miscommunication higher up in the military, Lee ended up at the battle of Saint-Malo in August 1944 where she witnessed the American siege on the German-held port and witnessed the first use of napalm bombing. Typically, women correspondents were not allowed to be on the front lines, making her presence as the only photojournalist - male or female- at Saint-Malo during the assault even more remarkable. It didn’t take the U.S. military long to find her, and her unauthorised presence resulted in her being placed under temporary arrest and later barred from the front line. This of course did not deter her from reporting elsewhere on the atrocities in Europe.

Lee Miller in a steel helmet specifically designed for using a camera, Normandy, France 1944. © Lee Miller Archives, England

During Lee’s work with Vogue, it became her goal to “document war as historical evidence”. In 1945, Lee wrote to Audrey Withers, “I don’t usually take pictures of horrors. But don’t think that every town and area isn’t rich with them.” She wanted the public to not just see but believe what was happening in the war.

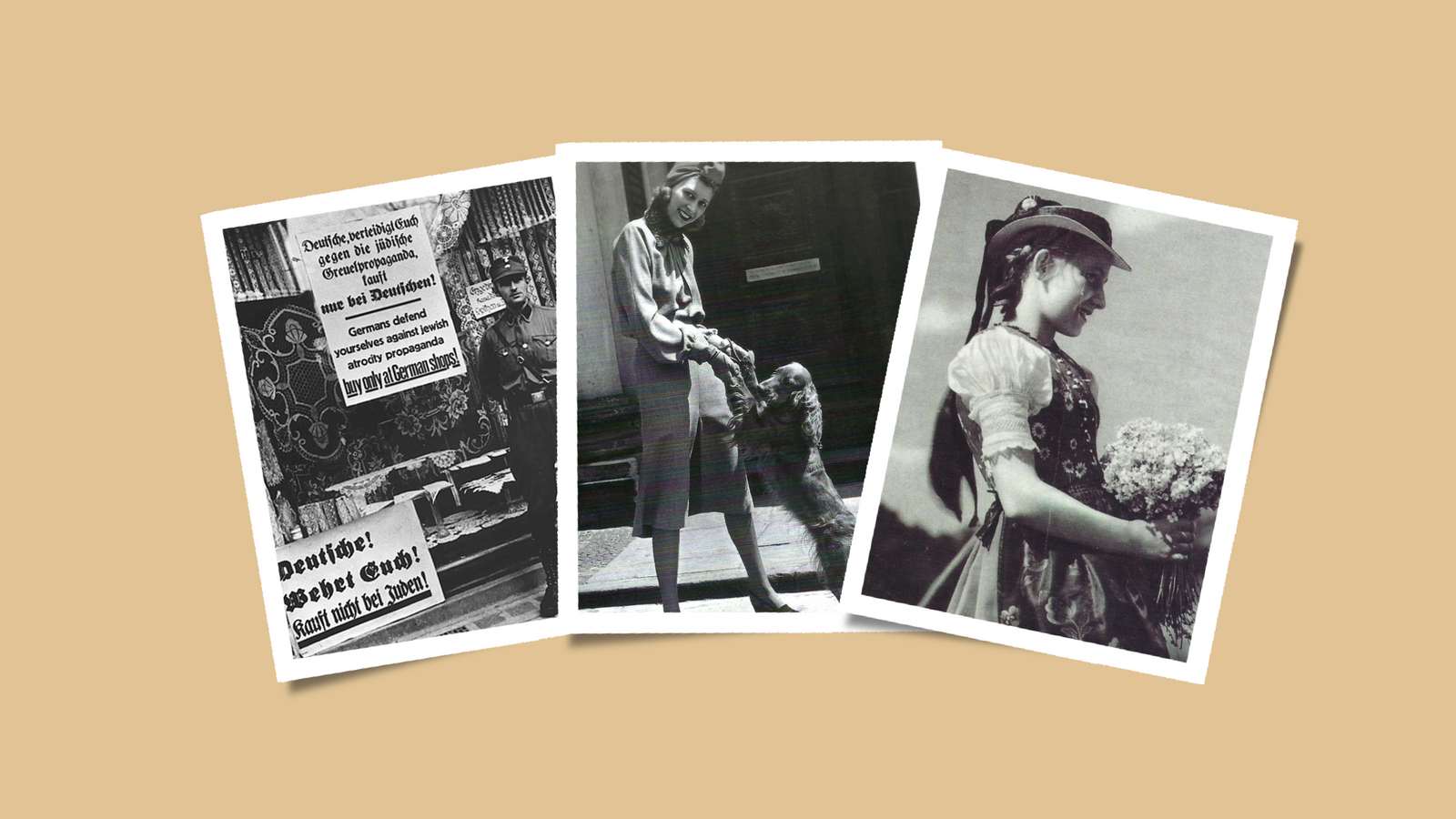

Miller’s lens bore witness to the liberation of Paris, the battle of Alsace, and the liberation by the U.S. of Nazi concentration camps at Buchenwald and Dachau - providing a haunting visual record of the Holocaust. Sending telegrams again to Withers, Lee urged Vogue to publicly publish her photos of the concentration camps, writing “I IMPLORE YOU TO BELIEVE THIS IS TRUE!”. Miller’s photos captured the proof that the world needed to see, and they were cold, hard evidence for disbelieving American and British audiences, who saw many written accounts of the war as propaganda. These wartime photos are likely to be the most graphic Vogue ever has or will have printed inside its glossy pages.

One of the most iconic images from this time of Lee’s life wasn’t a photo taken by her but by fellow war correspondent David E. Scherman. Scherman captured a photo of Lee in Hitler’s bathtub on the 30th of April 1945 - coincidentally the day of Hitler’s suicide. The pair had been one of the first to arrive at Hitler’s Munich apartment when she shed her clothes and created the iconic image. The photos can be read as a victory over a dictator and a reclamation of power by a long-objectified muse.

Lee Miller in Hitler's bathtub, photographed by David Scherman. © Lee Miller Archives, England

Her work during this period, including the iconic photograph of her bathing in Hitler’s bathtub, showcased her ability to juxtapose the horrors of war with moments of surrealism, offering a unique perspective on the human experience amid the chaos.

After the war, Lee continued to work as a photographer for Vogue covering much tamer topics of fashion and celebrities. But the images of war, especially concentration camps, continued to haunt her, and she started on what her son, Anthony Penrose, described as a “downward spiral”, struggling with depression and PTSD. For some respite, Lee and Roland Penrose travelled to California to visit Man Ray but was surprised to find she was pregnant by Penrose with her only son, Anthony. Swiftly, Lee divorced Bey (even after leaving Egypt she hadn’t divorced) and married Penrose before giving birth to Antony on the 9th of September 1947. Unfortunately, Lee’s struggle with mental health did not improve with her new marriage, and her depression may have further been accelerated by Roland’s long-term affair with acrobat Diane Deriaz.

Picasso and Lee Miller's son, Antony Penrose at Farley Farm, 1950. Photographed by Lee Miller. © Lee Miller Archives, England

Lee and Roland went on to buy Farley Farm House in Chidingly, East Sussex, which became host to their artistic friends, including Picasso and Man Ray, which sustained her connection to the creative community. During this time Lee stepped away from photography and instead took up cooking - with her granddaughter Ami Bouhassane publishing a book containing Lee’s recipes in 2021.

Miller passed away from cancer at Farley Farm House in 1977, aged 70. She hadn’t done much to publicise her work throughout her life, and the main reason her work is known today is due to her son, Antony, who has been studying, conserving, and promoting his mother’s work since the 1980s. He discovered an extortionate amount of photographs, negatives, documents, journals, cameras, love letters, and souvenirs in cardboard boxes and trunks in the attic of Farley Farm after his mother's passing.

Lee Miller at Farley Farm. c1960 © Roland Penrose

Miller once spoke of a “restlessness” that defined her career, and that may account for the variety of roles she occupied throughout her life. She was a model, a muse, a fashion photographer, a war correspondent, and gracefully moved from one version of herself to the next. Her ground-breaking work paved the way for future generations of female photographers, challenging societal norms and proving that women could excel in male-dominated fields, and reminds us that behind every lens there is a unique story waiting to be told - and Miller’s story continues to captivate and inspire.

Further reading on Lee Miller:

The Lee Miller Archives:https://www.leemiller.co.uk/component/Main/17ToA3p1yfaBss9G2InA3w..a

Lee Miller: Dressed (An exhibition at Brighton Museum, UK, running until 18th February 2024):https://brightonmuseums.org.uk/event/lee-miller-dressed/

Farley Farm House & Galleryhttps://www.farleyshouseandgallery.co.uk/people/lee-miller/

Imperial War Museum:https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/lee-millers-second-world-war

An interview with Antony Penrose, Lee Miller's son: https://www.cinegirl.net/home-all-issues/lee-miller-surrealist-war-photojournalist-model-cook-and-mothernbsp

Adrian Collins

October 04, 2025

A superb story that inspires you to embrace and get the most out of life’s rich tapestry. A truly extraordinary woman in everything she did, thank you to her son Anthony for carrying his mother’s torch to illuminate our lives still.