During WW2, the socio-political climate and necessities of war profoundly influenced the fashion in Germany. The Nazi regime sought to mould every facet of German life, including women’s attire, to reflect its ideals and expectations. This period saw a blend of state-imposed directives, resource scarcity, and subtle forms of resistance manifested through fashion choices.

Pre-WW2 late - 1930s Germany

The rise of the Nazi Party in the 1930s saw a change in attitudes towards fashion in Germany, with the regime seeking to control all aspects of fashion and appearance. Hitler envisioned Germany as the new fashion capital of the world, knocking France from its pedestal as world fashion leader. This vision led to the creation of the ‘Deutsches Modeamt’ (German Fashion Board) which aimed to influence women’s appearance and ensure that German fashion reflected nationalist ideals rather than foreign Parisian trends - but these ideals weren’t popular with German women.

Despite the push for German-made fashion, many wives of influential Nazi officials continued to wear French and other foreign styles, demonstrating the limitations of the regime’s influence within its ranks. Magda Goebbels (wife of Nazi Germany's Propaganda Minister, Joseph Goebbels) and Emmy Göring (wife of Luftwaffe Commander-in-Chief, Hermann Göring) were socialites obsessed with having the latest designer fashion who continued to buy the latest Parisian trends and from Jewish couturiers and stores until 1938.

Magda Goebbels. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The Deutsches Modeamt worked with German fashion magazines and designers to increasingly discourage women from buying French styles, arguing that the ever-changing Parisian fashions were wasteful with textiles and were influenced by Jewish designers, whom the regime wanted to eliminate from the industry completely. Purchasing and wearing German-made became a symbol of patriotism and ideological commitment to the regime.

1941 illustration from a German magazine, showing influences of folk wear

Source: Forties Fashion by Jonathan Walford

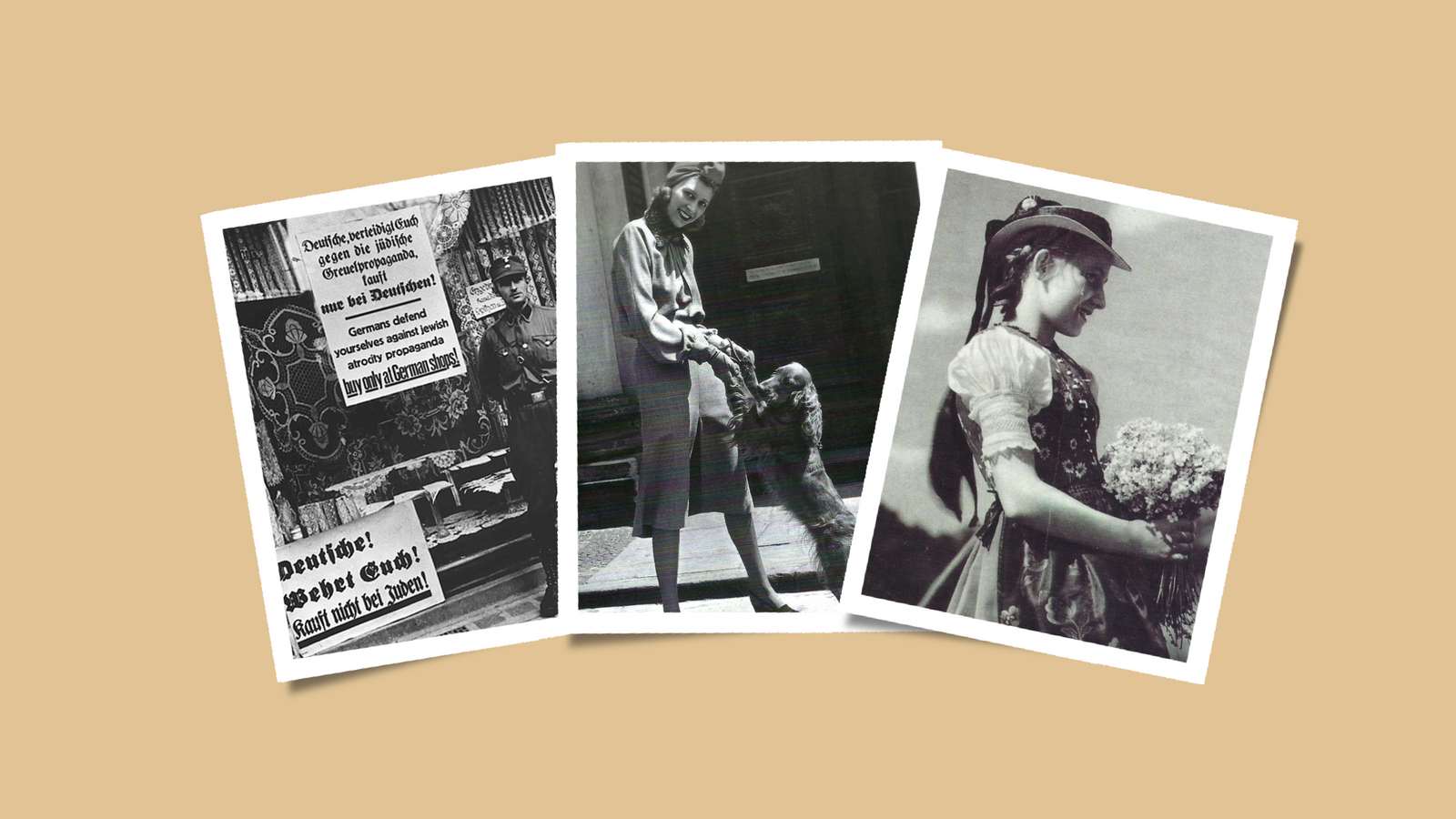

To solidify patriotism in fashion, traditional German styles such as the dirndl dress were promoted as the ideal garment for women to show her support for her country. The dirndl dress was a modest design, with long hemlines and wrist-length sleeves - the exact opposite of the tighter dresses with raised hemlines popular in other Western countries in the mid/late 1930s. Propaganda Chief Joesph Goeballs issued posters to showcase what the Nazis thought the ideal woman should look like, blonde beauties wearing their traditional dirndls - but the style didn’t catch on initially with German women. In an attempt to keep the support of women on the home front, the Nazis continued to allow German magazines to feature French fashions and cosmetics. Of course, this immediately stopped as soon as the war began in 1939.

The NS Frauen-Warte, a Nazi women's magazine, featuring the ideal 'Black Forest Maiden', 1943.

Source: Forties Fashion by Jonathan Walford

Despite Germany wanting to become the new fashion capital, it dealt itself a tremendous blow to this dream. 1935 saw the Deutsches Modeamt began enforcing the Nuremberg Race Laws, which excluded Jewish designers, manufacturers, and retailers from the fashion industry. By doing so, Germany removed a significant portion of the skilled German workforce that had held up the German fashion industry. Jewish professionals and artists were vital in textile manufacturing, fashion magazine publishing, and couture design. Their forced removal severely impacted the quality and global competitiveness of German fashion, and the country did not have the resources to replace these skilled workers. The vision for a self-sustaining fashion empire crumbled before it began, and the resource shortages from the war would tighten the noose.

The Nazi boycott of Jewish businesses, 1935. The posters instruct shoppers "Germans! Be on your guard! Don't buy from Jews!"

© Wiener Library

Wartime Fashion and The Nazi Vision of Womanhood

As the war raged on, Nazi Germany reinforced its rigid gender roles through fashion. Fashion adverts of the early 1940s depicted curvaceous, domestic women rather than independent figures in practical attire like trousers which were rising in popularity in America. Styles emphasised the ‘biological femininity’ with curvaceous models that defined them as mothers and homemakers - and always with the underlying idea that they needed to look pleasing to the men in their lives. Regardless of class or profession, women were expected to embody the idealised maternal figure of the Third Reich.

Nazi propaganda photo showing a mother with her daughters and her son in the Hitler Youth uniform. Posed for the SS-Leitheft magazine, 1943

Cosmetics were also a point of contention within the Nazi regime. They wanted a return to what they considered ‘traditional’ German values with a focus on women's natural beauty. Women were expected to look youthful, fit, and fertile - an appearance hard to maintain during the hardships of wartime. Blonde hair and blue eyes were preferable, but not essential. Alcohol, smoking, and excessive makeup were discouraged. Hitler had such a disdain for red lipstick that cosmetic companies in the UK and US jumped at the opportunity to advertise their products as a symbol of a “free society worth defending” in defiance of Hitler himself. If a woman did have to purchase cosmetics, she was expected to be a ‘good German’ by purchasing only German products.

Although heavy cosmetics were discouraged, the regime recognised the importance of women maintaining a vibrant appearance for both morale and their vision of the ideal woman. Adverts in NS-Frauen-Warte (National Socialist Women's Monitor), the official Nazi women’s magazine, encouraged the subtle use of makeup. Tips were given on how to conceal dark circles and other indicators of suffering from the war. A woman had to be attractive without appearing painted.

In 1943, Joseph Goebbels threatened to close all beauty salons in the country. At the behest of his companion Eva Braun, Hitler intervened in Goebbels's plans as he understood that beauty care was essential for morale. However, behind the scenes, Hitler instructed Albert Speer (Minister of Armaments and War Production) to halt the production of cosmetics and repurpose the chemicals used in permanent-wave hair treatments for the war effort. Italian dictator and ally of Germany, Benito Mussolini, famously stated in 1930:

“Any power whatsoever is destined to fail before fashion. If fashion says skirts are short, you will not succeed in lengthening them, even with the guillotine”

Maybe Hitler should have heeded this advice.

Italian fashions by Fercioni of Milan, illustrated in the German magazine Elegent Welt, 31st March 1939.

Source: Forties Fashion by Jonathan Walford

The first Kleiderkarte (clothing ration card) was introduced to regulate the distribution of clothing. Though initially confusing to the German public due to the points system, it later served as a model for the British rationing system. The point-based system initially had 100 points, usable in stages, but certain items - like leather shoes - required proof of necessity. To buy a new pair, individuals had to formally declare ownership of no more than two pairs, one of which had to be beyond repair. Inspections ensured compliance and any undisclosed pairs were confiscated and fines were imposed.

The fourth ration book, issued January 1943. This book was intended to last until June 1944, but was discontinued in August 1943 for lack of supplies.

A second clothing card was issued in 1940 and promised increased value by raising the allocation to 150 points. However, this increase was deceptive - clothing prices were adjusted to absorb the extra points, negating any real benefit. Each subsequent card became less valuable, offering fewer points with longer waiting periods. By August 1943, clothing ration cards were discontinued entirely.

A fashion image by Rolf-Werner Nehrdich, Berlin, c 1941-42. Most German highstreet fashions appearing in German magazines were labelled as 'unavailable until after the war' and were made only for export to neutral, occupied, and aligned countries.

Source: Forties Fashion by Jonathan Walford

With textiles being funnelled into the war effort, shortages in clothing became even more severe. The end of clothing rations in 1943 meant that getting new clothes was almost impossible. Fashion magazines encouraged women to refresh their wardrobes through accessories, particularly hats. The 1940 slogan ‘Alles ist Hut!’ (The hat is everything!) evolved into ‘Altes Kleid - neuer Hut’ (Old dress - new hat).

Women’s magazines offered articles and photo instructions on restyling older clothing, how to make clothes warmer, cooking meatless meals, making baby clothes, and generally economising the household. The slogan ‘Aus Alt Neu’ (From Old Make New) was Germany’s version of ‘Make Do and Mend’; but the lack of needles and sewing thread prevented German women from undertaking many of the projects suggested in magazines.

1941 German hats. Throughout the war, millinery had the fewest restrictions, least rationing and most novelty of any type of garment.

Source: Forties Fashion by Jonathan Walford

Sanitary napkins ceased production, and soap became a rare commodity with only 60 grams of soap allocated per person per month. Shampoo quality declined, and with no access to hair dyes or permanent treatments, women resorted to creative solutions like turbans or high-stacked hairstyles to hide unclean hair. The ‘Entwarnungsfrisur’ (all-clear hairdo) became a popular and practical wartime hairstyle.

The demands of wartime labour would see women eventually joining the wartime labour force. Overalls, jumpsuits, trousers, and culottes became more common as more German women entered the workforce. However, unlike Allied countries, Nazi propaganda did not actively recruit women for war-related duties until Germany declared total war in 1943. Even then, the expectation remained that women would return to their roles as wives and mothers once the war ended.

German work clothes fromNeue Moden, 1941.

Source: Forties Fashion by Jonathan Walford

To alleviate some the public struggle with clothing shortages, the regime would take the possessions stripped from the new arrivals of concentration caps which would be sorted and redistributed - some to bombing victims, some to soldiers, and some recycled into new textiles. Female SS guards and wives of Nazi officers often took the best pieces for themselves.

Women in Nazi Germany’s Universities and Workplaces

As mentioned above, the regime sought to confine women to traditional roles as wives and mothers. Universities, once open to ambitious women, became increasingly inaccessible. By the late 1930s, female enrollment was slashed to just 10%. Those who did study were often directed toward fields deemed suitable for women, including home economics and teaching rather than medicine, law, or engineering.

University students did resist the exclusion of women, and groups such as the White Rose were founded in 1942 by students Sophie Scholl and her brother, Hans. This non-violent group distributed leaflets condemning Nazi atrocities, including the treatment of the country’s women. In February 1943, Sophie and her fellow members were arrested for distributing anti-Nazi leaflets at the University of Munich and were unfortunately executed shortly after. The regime squashed down any resistance to their ideals.

Workplace restrictions were harsh. Women were systematically pushed out of higher-paying jobs and leadership roles, replaced by men or encouraged to leave work entirely to focus on raising families. Although war created labour shortages, Nazi ideology prevented the full mobilisation of women in the workforce, unlike Allied countries. Only in 1943, when Germany faced imminent defeat, did the regime reluctantly encourage more women to enter war-related industries - but always as a temporary measure.

Fashion Under Nazi Occupation

In June 1940, France surrendered to Nazi Germany. Many within the Reich saw this as an opportunity to eliminate Parisian fashion dominance and elevate German designs. The French Vichy government, seeking to avoid destruction, handed over Paris to Hitler. However, many French designers were making moves to save their industry.

Lucien Lelong, designer and then president of the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture (governing body for the French fashion industry) convinced Nazi officials that the fashion industry was too valuable for them to dismantle. He argued that preserving it would not only protect French jobs but also serve as part of Hitler’s spoils of war. As a result, Parisian fashion houses continued producing two collections a year, primarily clothing Nazi officer’s wives and privileged women of Germany’s allies.

The first spring collection after the German occupation of France. The designs were a 'safe' collection of useful and easy-fitting clothes with separates for versatility. This illustration was featured Modes et Travaux

Source: Forties Fashion by Jonathan Walford

During the German occupation, several high-profile designers operated in morally grey areas, navigating the war through compromises to protect themselves and their employees. Some openly collaborated with Nazi officials.

Hugo Boss - A Designer for the Reich

Although not a French designer, Boss was still a well-established and renowned name within the fashion world. Hugo Boss was an early supporter of the Nazi Party, joining in 1931 - two years before Hitler rose to power. His company produced uniforms for the SS (although did not design these uniforms, only made them), Hitler Youth, and the notorious brownshirts. By 1938, as Germany intensified its military efforts, Boss’s factories expanded to produce uniforms for the armed forces. The company used forced labour from concentration camp prisoners to meet demand with exceptionally poor work conditions. Post-war, Boss was classified as an “opportunist” by de-Nazification tribunals and was fined for his involvement within the regime.

Hitler Youth in a uniform designed by H. Boss. Photo: Bundesarchiv, Bild 119-5592-14A / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Coco Chanel

A household name in fashion, Chanel made a shocking decision during the German occupation of France - she shut down her fashion house entirely. More controversially, she became involved with senior Nazi official Hans Günther von Dincklage and moved into the luxurious Ritz Hotel, which was favoured by high-ranking German officials.

Chanel’s ties went beyond her personal life. She allegedly sought to use anti-Semitic laws to regain full control of her perfume company, which was partly owned by a Jewish family. She was also known to be a German Intelligence Operative and was known by her Nazi handlers as agent F-7124. After the war, she was arrested for collaboration but was released, reportedly due to intervention from Winson Churchill. Despite her wartime activities, Chanel later relaunched her brand, erasing much of her controversial past from public memory.

Lucien Lelong and Christian Dior

Lucien Lelong fought to keep the Parisian fashion industry from being uprooted. He argued that moving French couture to Berlin, as some Nazi officials proposed, would be disastrous. Lelong argued that the craftsmanship and expertise that had been cultivated over generations could not be replicated elsewhere, and the manufacturing infrastructure was too established to relocate. Thanks to Lelong's insistence, he saved the livelihood of the 12,000 workers employed by Lelong, although he had no choice but to design for Nazi officials.

Sketch by Dior whilst working for Lelong, 1944.

© All rights reserved. Dior Héritage collection, Paris.

Christian Dior, then a young designer working under Lelong, played a more risky role. While he dressed the wives and mistresses of high-ranking Nazi officials, his sister, Catherine Dior, was an active member of the French Resistance. Catherine would use Christian’s apartment as a site for resistance meetings, putting both of them in a great deal of danger. Catherine was later arrested and tortured by the Gestapo in Paris in 1944 before being denounced as a résistante and deported to Ravensbrück, a concentration camp in northern Germany. With his connections in French society and German officials, Christian attempted to have his sister released but to no avail. Catherine remained at Ravensbrück until the liberation of the camp in 1945.

The Liberation of Paris

When Paris was liberated in August 1944, many of the fashion industry’s secrets were exposed. Some designers faced trials for collaboration, while others quietly continued their careers. Coco Chanel fled to Switzerland for 10 years to avoid criminal charges of collaboration but eventually returned to Paris to revive her fashion house. Hugo Boss’s company faced legal consequences, and even potential collaboration between the Nazis and Louis Vuitton was swept under the rug with evidence conveniently going missing or burnt.

Paris, however, retained its status as the world’s fashion capital. Designers like Christian Dior, who launched his revolutionary ‘New Look’ in 1947, helped to restore the industry’s reputation and revive the glamour of haute couture after years of hardship.

Youth Subcultures resisting Nazis

While the Nazi regime sought to indoctrinate German youth through organisations like the Hitler Youth, several groups of young people came together in defiance of Nazi ideology. Notable amongst these were the Edelweiss Pirates and the Swing Kids, groups that resisted conformity and embraced alternative lifestyles, often at great personal risk.

The Edelweiss Pirates

Originating in western Germany during the late 1930s, the Edelweiss Pirates consisted mainly of youths from the working class aged 14 to 18. They rejected the strict discipline and militarism of the Hitler Youth, favouring instead a lifestyle that celebrated freedom and individuality. Identifiable by their edelweiss flower badges, these groups engaged in activities such as hiking, camping, and singing songs that often parodied that of Hiter Youth marches. They advocated for a space where boys and girls could mix freely, contrasting sharply with the Nazi emphasis on gender segregation through the Hitler Youth and the female equivalent, the League of German Girls (a unit set to remind girls that their place was strictly at home).

"These adolescents, aged between 12 and 17, hang around late in the evening with musical instruments and young females. Since this riff raff is in large part outside the Hitler Youth and adopts a hostile attitude towards the organisation, they represent a danger to other young people." - Nazi Party Report, Dusseldorf, Germany, July 1943.

Source: Metal Floss/NSDOK

As the war progressed, the Edelweiss Pirates’ resistance became more pronounced. They assisted army deserters, distributed Allied propaganda leaflets, and, in some instances, engaged in acts of sabotage against Nazi operations. Nazi authorities responded with increasing brutality; members were arrested, and some were executed. In November 1944, thirteen individuals associated with the Edelweiss Pirates in Cologne were publicly hanged, underscoring the severe risks these youths faced in their defiance.

The Swing Kids

The Swing Kids (Swingjugend) were a group of jazz and swing enthusiasts in major German cities like Hamburg and Berlin. Drawn to American and British swing music, these youths embraced a culture that stood in stark contrast to Nazi ideals. They adopted distinctive fashion styles, with boys wearing long hair, homburg hats, and carrying umbrellas, while girls donned short skirts and applied makeup - choices that defied the conservative norms imposed by the regime.

The Swing Kids organised dance events in private venues, where they could freely express their passion for forbidden music genres, and their gatherings became an act of non-conformity. Although not overly political, their open rejection of Nazi cultural politics marked them as subversive and were treated as a threat, resulting in some Swing Kids being arrested with leaders sent to concentration camps.

Post War

Post-war Germany faced immediate and immense challenges, as necessities like food and shelter took precedence over fashion. New clothes would come eventually in a show of creativity from the German fashion industry. The first post-war fashion show in Berlin on the 9th of September 1945 introduced the ‘Flickenkleid’ (patch dress). This dress was created from an array of salvaged materials, including blankets, curtains, uniforms, and tablecloths. Sugar sacks were unwound and used to crochet gloves, and handbags were woven from gas mask straps which served as accessories to the patch dress. The fashion wasn’t anything groundbreaking, but the event symbolised resourcefulness and reflected the nation’s determination to rebuild.

The Flickenkleid. Source: Art Library. State Museums of Berlin.

World War 2 was not only a time of global conflict but also a period of deep social and cultural struggle, especially within Nazi Germany and its occupied territories. Women’s fashion, once a reflection of personal expression, became a tool of propaganda, reinforcing rigid gender roles while adapting to the harsh realities of wartime shortages. The Nazi regime imposed severe restrictions on women’s education and employment, confining them to traditional domestic roles and stripping them of opportunities for independence. The stories of wartime fashion, political restrictions, and underground resistance paint a broader picture of life under the Nazi regime. They reveal how culture, identity, and defiance persisted in the face of dictatorship.

Sources:

Forties Fashion: From Siren Suits to the New Look byJonathan Walford

Fashion Under the Swastika: An Analysis of Women’s Fashion During the Third Reich

The Fashion History of the Dirndl - The Pink LookBook

Fashion and The Third Reich - History Today

How Hitler Influenced 1940s Fashion - We Heart Vintage

Sophie Scholl and the Legacy of Resistance - JSTOR

Haute Couture During WW2 - Refashioning History

Hugo Boss and the Nazis - Jewish Virtual Library

Was Hugo Boss Hitler's Tailor?

Five Big-Name Fashion Designers Who Had Ties to the Nazis - The Fashion Spot

Coco Chanel’s Secret Life as a Nazi Agent - Biography

How Youth Subcultures Resisted the Nazis During World War 2 - Teen Vogue

Meet The Edelweiss Pirates: The Little-Known Teenaged Resistance Fighters of Nazi Germany

“Swing Heil”: Swing Youth, Schlurfs, and others in Nazi Germany

JL Merrow

March 31, 2025

Amazing article! There is so much in this I didn’t know. I wish this tale of bigotry and misogyny didn’t feel so relevant today.