The silk scarf is an absolute iconic fashion accessory of the forties and fifties - whether around your neck or in your hair, a silk scarf was a must-have for completing many outfits!

Silk was high in demand in both fashion and wartime production, helping save the lives of thousands of soldiers during the war whilst also keeping the ladies at home safe in their new manual labour positions. But just how did silk keep Britain safe in the Second World War?

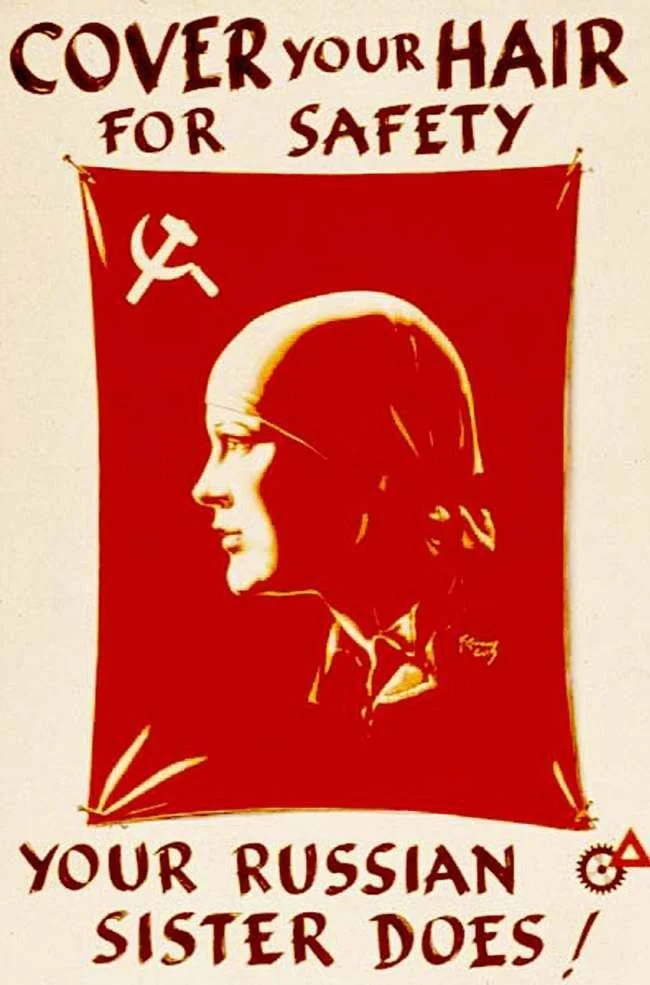

The humble silk scarf had been popular through the 1930s and 1940s, but the war gave the scarf an even higher pedestal to sit on. The neck scarf quickly adapted to be the headscarf for many women, a necessity of wartime frugality and innovation.

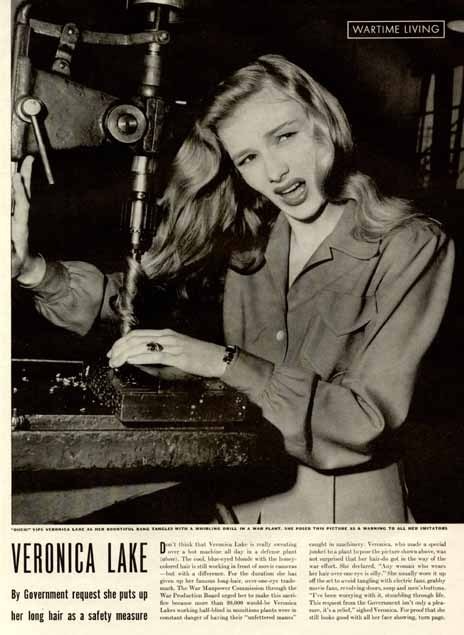

With so many women taking up the positions left vacant by conscripted men, women needed something which protected their hair in the workplace. Longer hair could easily be caught in machinery, and any debris or dirt could easily find its way into ladies' hair, all in all, hair was just a big health and safety concern at the time.

Factory workers with their hair up.

Health & safety committees, fashion editors, and even celebrities helped influence women’s fashion so that the scarf would be seen as an essential part of a woman's daily uniform. Scarves were shown as a practical, yet fashionable way to protect hair in the workplace and quickly became a staple for many women around Britain and America.

Veronica Lake with her hair caught in a drill. This American advert advised women to put their hair up at work for safety.

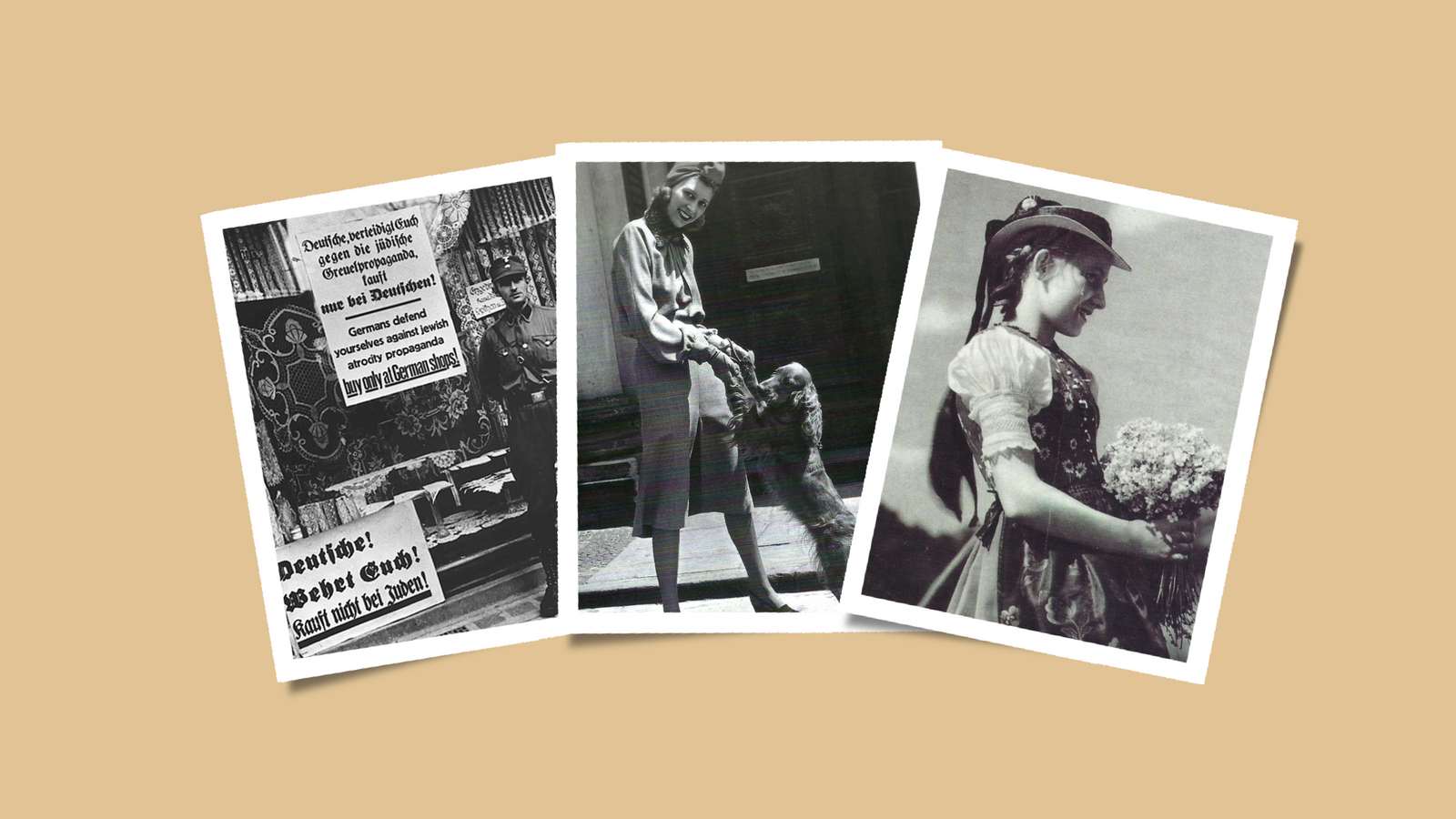

Thanks to the propaganda schemes of the British Government, headscarves quickly became associated as a symbolic and patriotic piece of clothing. The headscarves showed that women were doing their part and working for the war effort, and set a fashion trend for the whole decade.

Although silk was the most luxurious fabric to make these scarves from, rayons and crepes became the wartime alternative to silk and provided the exact same comfort and workplace protection but cost a lot less!

The British Government put up posters saying “Cover your hair for safety - like your Russian sister does!” to promote the use of headscarves, but also adding in a bit of comradery with the allied Russian women who were in similar working situations. The US had their own version of this with the famous “We Can Do it!” with Rosie the Riveter being a beacon of patriotism and empowerment for women.

The make-do-and-mend movement in Britain also encouraged women to repurpose fabric into headscarves to save fabric, rations and money. Fashion press such as Vogue also ran features that encouraged headscarves as part of women’s war efforts and also showcased the latest popular workwear and new propaganda prints.

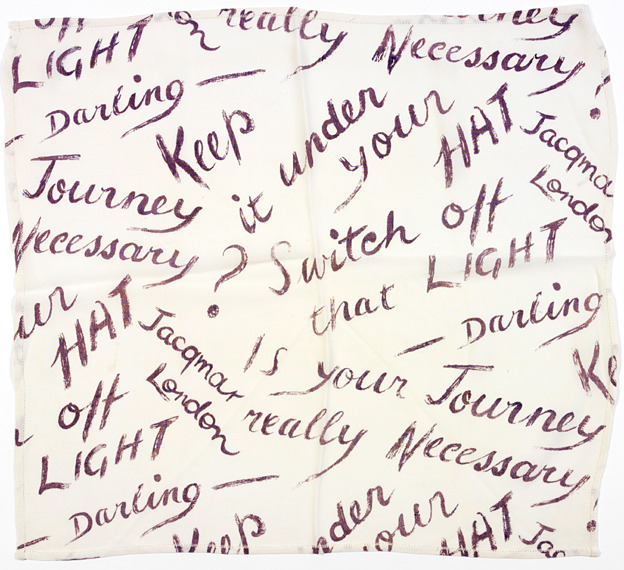

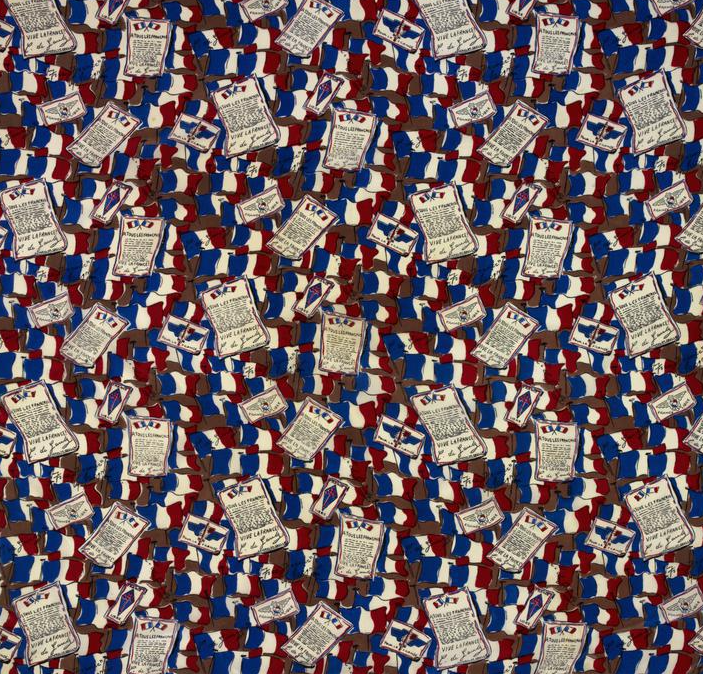

Propaganda prints were so important for home front morale and propaganda scarves in particular were vehicles for displaying patriotic idioms, wartime illustrations, and advertisements. Silk propaganda scarves have become so valuable today that they are often exhibited in museums and are prized by collectors as they’ve become valuable pieces of artwork from the war era.

JACQMAR SILK SCARVES

One company in London was behind the surging popularity of propaganda scarves throughout the war. Originally founded in 1932 as a fabric shop, Jacqmar was founded by Joseph “Jack” Lyons and his wife Mary Lyons who combined their names “Jack-Mar” to create the company name, intentionally done to sound quite French.

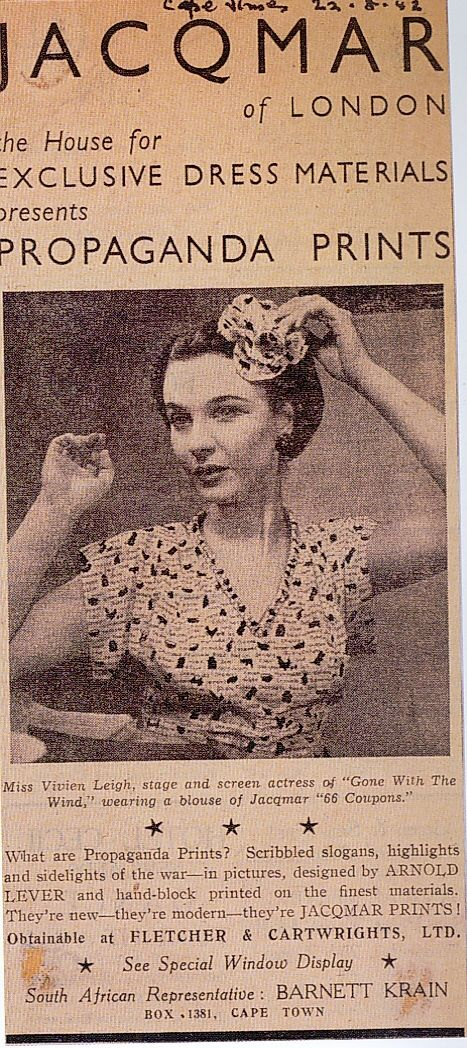

Jacqmar originally supplied silk to Paris before the war, using any offcuts to make scarves. These were instant hits in the fashion industry and Jacqmar quickly turned to specialise in scarf production and gained high-profile clientele including Vivien Leigh and Clementine Churchill, Winston Churchill’s wife. The company went on to make propaganda scarves throughout the war and were based in their prestigious Grosvenor Street address in Mayfair.

An advert for Jacqmar propaganda prints featuring actress Vivien Leigh. She wears matching propaganda print blouse and hair accessory.

When WW2 came around Jacqmar began to specialise further in propaganda prints to feature on their scarves. Their chief designer, Arnold Lever, created a range of patriotic and wartime-inspired designs and continued to design for the company even after he had joined the RAF!

Prints would often fall into three very distinct themes: the armed forces, the allies, and the home front. These designs allowed the public to show their support for the war without sacrificing their style. In 1945 Harper’s Bazaar wrote:

“Scarves were never more brilliant and varied. Used with ingenuity and imagination they enrich our scanty wardrobes and bring individuality to uniform clothes”

Jacqmar’s scarves were a hit with the British public, but also overseas too. Jacqmar advertised their scarves as “British Designed and British Made”, giving something for British people to be proud of and making their products desirable for allied countries abroad. In 1941 and 1942 the Cotton Board organised export trade exhibitions which skyrocketed Jacqmar’s exports to the US, South Africa, and South America. These exported products carried Britain’s propaganda messages to Allies and neutral countries all around the world. The propaganda textiles helped to strengthen sympathy and cooperative ties between nations, as well as being a much-needed infusion of foreign money into the UK.

A 1942 issue of Vogue advertised Jacqmar’s spring collection with a real emphasis on Jacqmar products being an excellent alternative to French designs which were no longer available to the international market after the occupation of France by Nazi forces in 1941 - again pushing that British products were just as good, if not better than what was once the fashion capital of the world.

Propaganda scarves were also excellent souvenirs and gifts which foreign servicemen bought for their sweethearts or British girlfriends whilst stationed in the UK, particularly in London. Jacqmar scarves were luxurious in quality, and quite expensive for what they were and not all could afford them. On top of their expensive price tag, the scarves also required two clothing coupons to purchase. With a dress requiring around 11 clothing coupons, it simply wasn’t a logical choice for many to splash out on when you could easily make your own scarf at home.

PROPAGANDA SCARF DESIGNS

Many designs for propaganda scarves were sometimes straightforward, sometimes whimsical, and sometimes humorous. One design featured the phrase “Shut that door, Darling” relating to the posters which encouraged the public to conserve heat in their homes, with another design featuring “Ouch! I’m So Sorry! Oy!- Why Not Wear Something White Instead?” from a campaign aimed at reducing accidents in blackouts by encouraging the public to wear lighter colours to be easily seen in the dark.

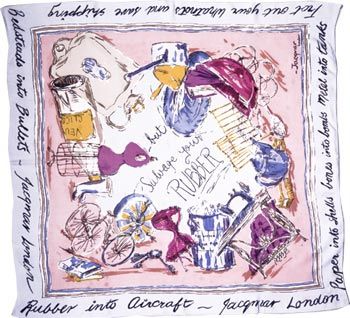

“Salvage Your Rubber” -encouraging the public to recycle and reuse materials. The illustrations on the scarf indicated some of the items that could be reused and made the wearer a walking recycling promotion.

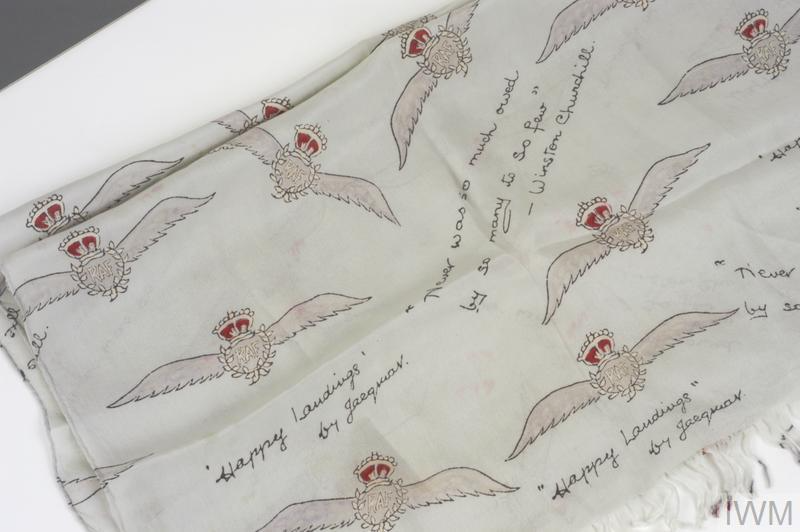

“Happy Landings” -a simpler, more intricate design featuring the RAF crest along with Churchill’s famous tribute to the RAF during the Battle of Britain: ‘Never was so much owed by so many to so few’.

American Forces in London - a design which showcased many of London’s historical sites. These kinds of designs were intended to appeal to American servicemen who may purchase a scarf for a loved one.

“Switch Off That Light”- another design featuring a message given to the public to encourage them to turn the lights off, especially during the Blitz.

Free French- a design featuring Free French flags and badges in support of the French forces that continued to fight Germany following the fall of France. The design featured a famous speech by Free French leader General De Gaulle.

OTHER USES OF SILK IN THE WAR

Although silk propaganda scarves were an excellent way to help maintain home front morale, silk also played a part in saving the lives of Allied soldiers.

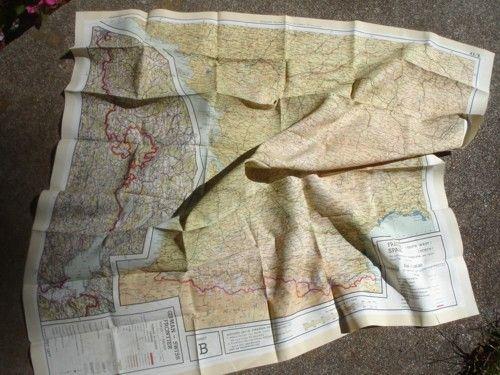

During the battles of WW2 there were always chances of British servicemen being shot down or captured and taken as prisoners of war in Europe and the Pacific. Paper escape maps were ultimately useless as soon as they came into contact with water, and could easily give your position away from the sound of being unfolded. These escape and evasion maps were invaluable tools for dangerous situations, so needed to be less of a hinderance to troops.

WW2 Silk Map

MI9 inventor Christopher Clayton Hutton worked with Wallace Ellison, a POW in the First World War, to figure out a way of fixing ink onto maps permanently regardless of water. Hutton and Ellison found that silk was the perfect material to use for escape maps. Silk was warm, durable, resisted creasing, and could be concealed under clothing easily. Hutton and Ellison found that by adding Pectin (a kind of acid found in plants and fruits) to the ink kept the dye from running or washing when immersed in water - even seawater. The silk maps were also completely silent when being unfolded.

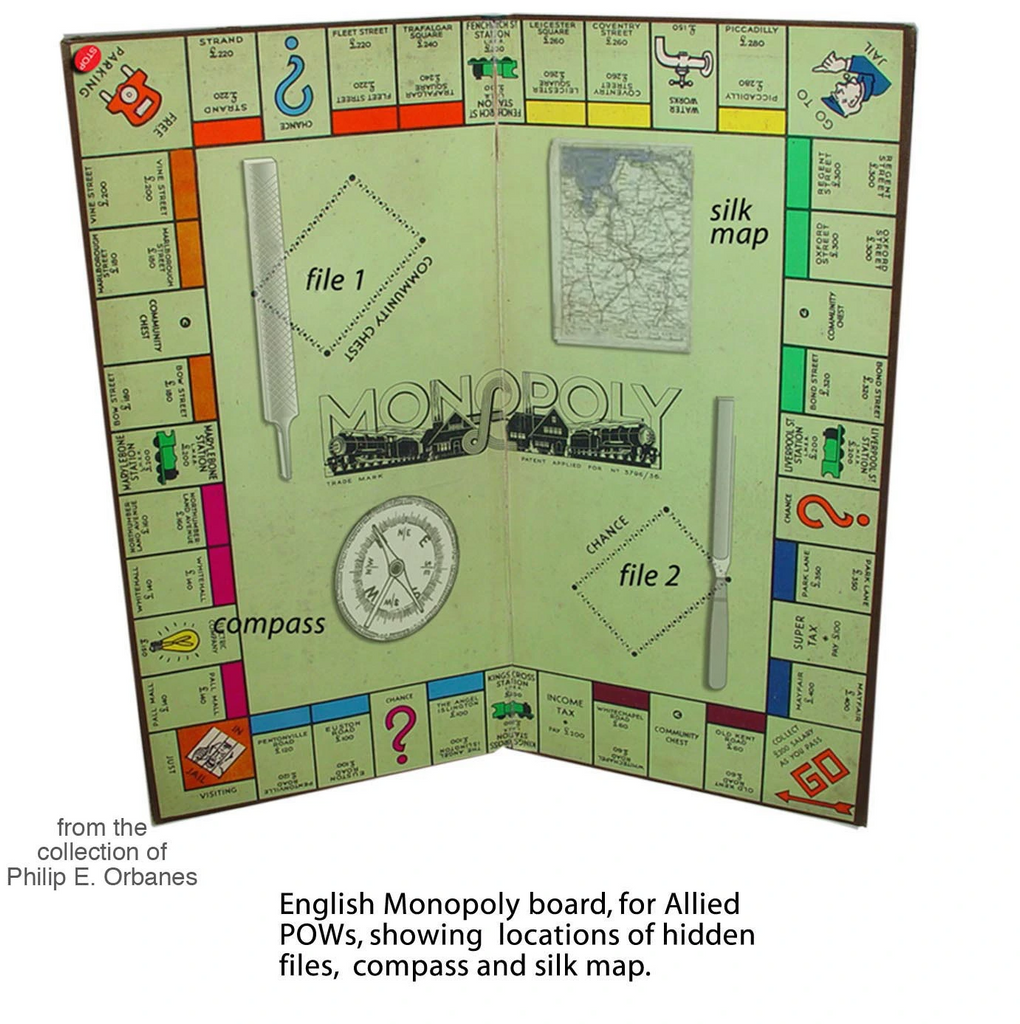

Hutton worked with John Waddington Ltd. worked together to print the silk maps in a small section of the factory. John Waddington Ltd. at the time manufactured all of Britain's Monopoly boards and worked out a way to strategically hide the silk maps within these boards. Before going on missions, RAF airmen were instructed that if captured they should look out for Monopoly boards sent to POW camps by charity groups. Humanitarian packages from UK charities would contain these specially made Monopoly boards containing ‘escape kits’ inside.

Marked by a dot on the car parking square on the board, these Monopoly boards would provide compasses, small metal tools, and silk maps detailing their respective locations and paths to freedom.

A WW2 Monopoly board showing the red indicator, and the hidden sections where a map and other escape tools were hidden.

Silk escape maps were also hidden in packs of playing cards as well as hollowed-out pencils and helped hundreds of British and US forces escape from the enemies. The maps were a real display of wartime creativity and resourcefulness.

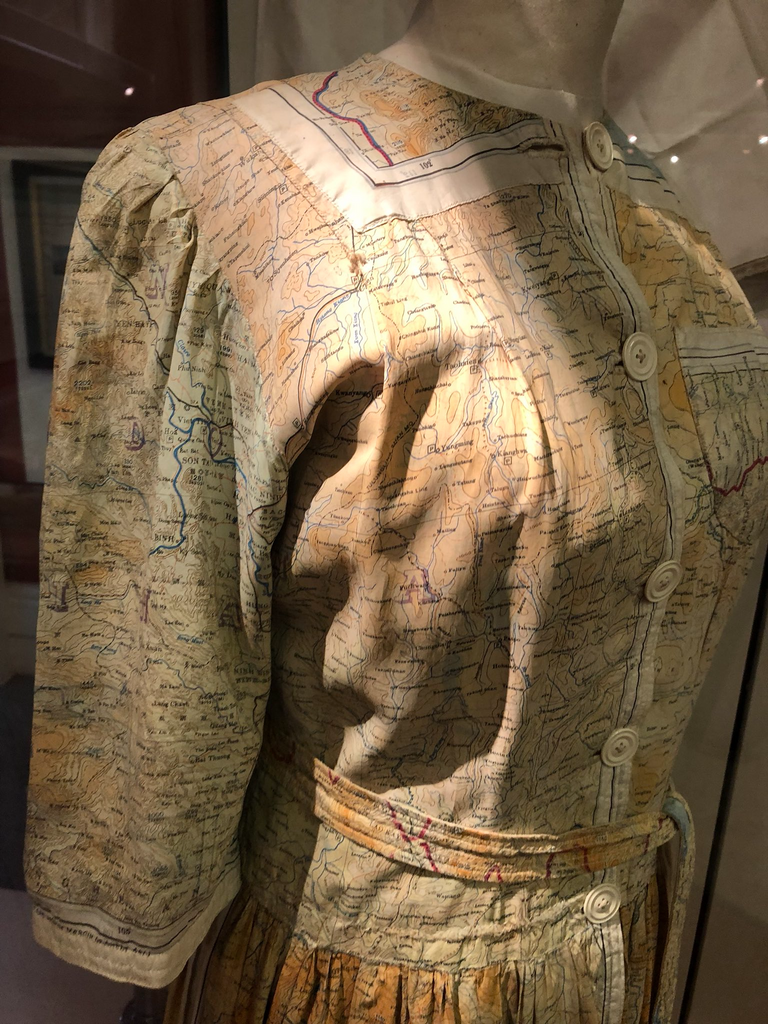

The silk maps were also popular on the home front too! Unlike other materials and fabrics, silk maps weren’t subject to coupon rationing and had no limit on how much you could purchase from army surplus stores due to the sheer amount of these maps that had been made (except how much money you had!). For the crafty minded it was easy to turn these relatively small maps into garments such as underwear, blouses, and rompers for children.

A dress made from silk maps. The maker used the edge of the map as a collar for the dress.

Silk parachutes also helped save thousands of airmen in the war, and were of course reused and repurposed after use. These parachutes were made out of pure silk due to its durable and lightweight nature and would be in a soft cream colour - perfect to be remade into clothing.

Once a parachute had been used and was deemed unfit for further use (usually damaged in the landing process or had been submerged in seawater) servicemen were allowed to take the parachutes home with them. Parachutes provided a huge amount of fabric which could easily be turned into clothing, and with the public thriving off make-do-and-mend many crafty individuals took matters into their own hands.

RAF parachute

With fabric rationing and restricted funds, it was incredibly difficult to find enough white or cream fabric for a wedding dress. Many brides in the war era had to make do with hand-me-down gowns, or simply go without. But a parachute changed the game entirely! There was enough fabric in a parachute for a crafty bride to make a full-length gown with puffy sleeves, and even a train if there was enough good-condition fabric.

There were stories up and down the country of brides who were making their wedding dresses out of the parachutes which had saved the lives of their husbands. Newspapers published stories about dedicated and fierce young women who were determined not to let any fabric go to waste. These young women became a symbol around the country for their resourcefulness and creativity, but also as an act to honour the service of these men.

Leslie Speller and Eileen Stone – Married 20 June 1945. Copyright IWM

“Eileen made her own wedding dress from one of Leslie’s parachutes. After the wedding, she cut up the dress, dyed it and used it to line a coat. She kept a piece of undyed silk to make an embroidered handkerchief. She also dyed a piece of the parachute cord and used it to bind a wedding album she’d made. The other pieces of cord were kept and used regularly for camping trips” .

Propaganda scarf with the make do and mend idioms.

Propaganda scarf with the Allied flags in a bouquet of flowers.

Propaganda print with common house hold ingredients.

Robin M

February 23, 2025

Great article! Have you thought about making the propoganda scarves? I would definitely buy several!