World War 2 was a time of unparalleled global conflict that demanded vast resources, innovation, and bravery. Amid the chaos and uncertainty, a remarkable group of women soared to new heights, establishing themselves in a field once dominated by men. These were the ATA girls, affectionately known as “Attagirls!”, whose contributions to the war effort were both essential and pioneering.

The 'First Eight' of the ATA Women's Section pilots walking past newly-completed De Havilland Tiger Moths awaiting delivery to their units at Hatfield, Hertfordshire. They are, (right to left): Miss Pauline Gower, Commandant of the Women's Section, Miss M Cunnison (partly obscured), Mrs Winifred Crossley, The Hon. Mrs Fairweather, Miss Mona Friedlander, Miss Joan Hughes, Mrs G Paterson and Miss Rosemary Rees. Copyright IWM (C 382)

As the war engulfed Europe, the demand for pilots grew exponentially. With many men enlisting in the armed forces, there was an emergent need for skilled pilots to ferry aircraft, conduct reconnaissance missions, and engage in combat. In 1939 when the war erupted, the aviation industry was still in its early stages, and only the rich could afford to travel via air. Amy Johnson’s solo flight from Croydon to Australia had captivated the world, turning flying into a fashionable hobby for wealthy women.

But the RAF was scrambling to increase its fleet and pilots and initially had completely written off the idea of female pilots, even for non-combat roles. To meet this demand for non-combat pilots, the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) was established in 1939. Originally, the ATA was intended to transport personnel, mail, and medical supplies. However, the pilots quickly became essential for working with the RAF ferry pools in transporting aircraft. By the 1st of August 1941, the ATA had assumed full responsibility for ferrying new, repaired, and damaged RAF aircraft between factories, maintenance units, and active service squadrons, thereby allowing frontline pilots to focus on combat duties. Between September 1939 and its dissolution in November 1945, the ATA made over 309,000 missions.

ATA flying instructor, Miss J Broad, with a male pupil in an Oxford training aircraft. Copyright IWM (E(MOS) 300)

As the war intensified and demand for pilots increased, the ATA broke new ground by recruiting female pilots, a revolutionary decision for its time. This move was partly due to the shortage of male pilots and partly driven by the belief that women could perform these non-combat roles just as effectively as a man.

Joan Hughes, an expert 'heavies' pilot. Here she is dwarfed by the giant Short Stirling she is about to ferry to an RAF airfield

Commander Pauline Gower was the trailblazer tasked with organising the women’s division of the ATA to combat the need for more pilots. Pauline gathered eight women for service on the 1st of January 1940, but they were only permitted to fly De Havilland Tiger Moths. The 'First Eight' pilots ferried the open-cockpit Tiger Moths in harsh winter conditions from Hatfield, near the De Havilland factory, all the way to Scotland as a test run. Though it was a modest beginning, within years, this group of female pilots would be flying all types of aircraft, from Hurricanes to Spitfires, to four-engine heavy Lancaster bombers.

Pauline Gower, 4th March 1940 at the Women's Engineering Society Awards Dinner. Copyright Women's Engineering Society Archives.

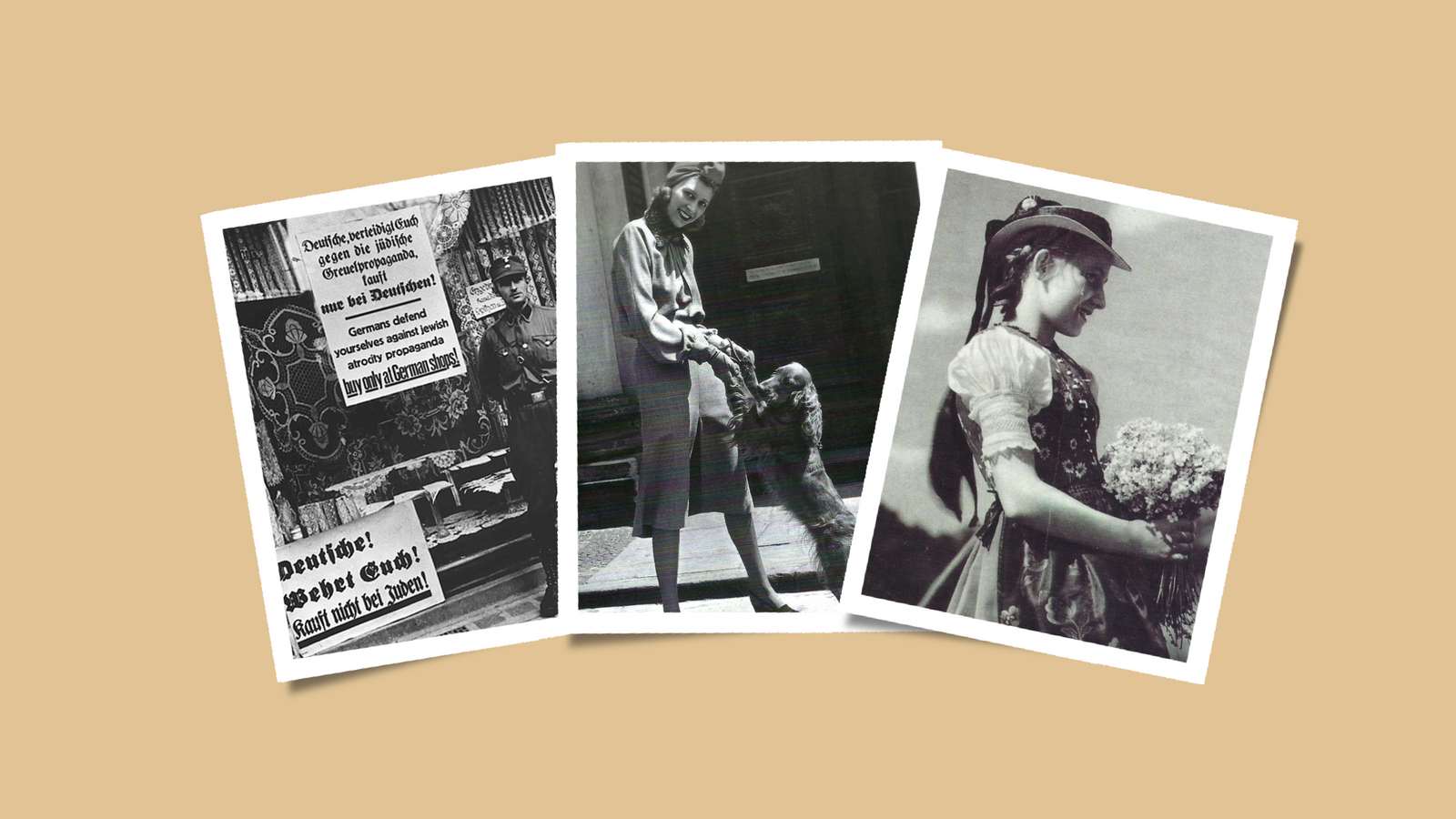

The inclusion of women in the ATA was met with scepticism and resistance from various quarters. Many doubted their ability to handle complex and powerful aircraft. The Attagirls were called “disgusting” and a “menace” by some, with RAF brass sharing these sentiments. An aviation magazine even harshly asserted, “The menace is the woman who thinks that she ought to be flying a high-speed bomber when she has not the intelligence to scrub the floor of a hospital properly.”

Pauline Gower (far left) with the 'First Eight'. Copyright IWM C389

However, the women quickly dispelled these doubts. They flew over 147 different types of aircraft, from more basic aircraft like the Tiger Moth to powerful fighters such as the Spitfire and heavy bombers.

First Officer Faith Bennett signs a collection chit for a new Spitfire at a factory.

The ATA was one of the few in the era to have an incredibly diverse workforce. As well as taking on female pilots, the ATA also accepted men who were disabled or unfit for active duty, older pilots, and foreign pilots (both men and women) from over 28 different nationalities. Astonishingly for the time, from 1943 onwards the British government allowed the women of the ATA to be paid the same wage as men of equal rank. Such equality had never been seen before in an organisation under the government's control and was an excellent move for fair wages, especially when American women flying with the WASP (Women Airforce Service Pilots) received as little as 65 per cent of their equivalent male colleagues.

WASP pilots. (From left to right) Frances Green, Margaret Kirchner, Ann Waldner, Blanche Osborn leave their B-17, called Pistol Packin' Mama, during ferry training at Lockbourne Army Air Force base in Ohio.

One fascinating thing about the Attagirls is that they essentially flew blind without radios and often without instruments. They displayed extraordinary skill and courage by navigating by using only a map, compass, and identifying landmarks in the British countryside. Women pilots didn’t receive the same training as RAF pilots as they were required to fly within sight of the ground rather than soaring at high altitudes. Some women made it their business to teach themselves how to use onboard instruments if they weren’t going to be taught, and some managed to secure sessions in an early flight simulator known as a Link Trainer.

Link Trainer in use at a British Fleet Air Arm station in 1943, Lee-on-Solent. Here budding pilots received their first training in blind flying while the instructor talks to them via a phone.

Despite not seeing combat, the work of a ferry pilot wasn’t without danger. 174 men and women ATA pilots were killed during the war, which was around 10% of the total pilots who flew for the ATA. Initially, the aircraft were ferried with unloaded guns and other armaments. However, after suffering from friendly fire (thanks to the lack of radio equipment to confirm their identity) and encounters with German aircraft, any RAF aircraft were ferried with guns fully loaded to offer a chance of defending themselves. The aircraft themselves were often damaged from combat and being flown for repairs, making some flights even riskier.

Mary Guthrie on the wing of a Spitfire Mark V.

Bad weather was especially deadly for ATA pilots, as navigating in the typically bad British weather pilots could be taken miles off course from their destination. Even the most seasoned were susceptible to bad weather. Amy Johnson (mentioned above) joined the ATA in 1940, and on a scheduled ferry flight on the 5th of January 1941, she veered off course due to poor weather conditions. After running out of fuel, she attempted to emergency land her aircraft in the Thames Estuary. Several ships on the estuary saw Amy’s plane and her cries for help from her parachute, and a Royal Navy officer even jumped overboard from his ship into freezing waters in a rescue attempt. Unfortunately, the officer was pulled from the water unconscious and sadly died two days later in hospital. However, Amy Johnson’s body sadly was never recovered, and the terms of her death are still disputed to this day.

Amy Johnson. Credit: PA Archive/PA Iamges

The Atta girls showed their dedication and proficiency and helped to change perceptions about women’s capabilities in aviation. Here are the stories from a handful of some of the brave female pilots.

PAULINE GOWER

Potentially the most prominent figure of the ATA was Pauline Gower, who was instrumental in advocating for the inclusion of women in the ATA in the first place. Gower, a seasoned pilot before the war, was appointed as the head of the women’s section of the ATA and played a crucial role in its development and success.

Born on the 22nd of July 1910 in Royal Tunbridge Wells, Kent, Pauline was the daughter of Sir Robert Gower, a prominent barrister and politician. She began flying in the 1930s and was one of the first women to run a commercial taxi service for those who could afford to travel by air. This venture was instrumental in showcasing women’s capabilities in aviation, laying the groundwork for her future endeavours. She was also a council member of the Women’s Engineering Society which was formed after the First World War. Pauline was keen to promote flying to other women, and often wrote pieces forGirls Own andChatterbox, and even published her own book -Women With Wings.

In 1938, Pauline (thanks to some of her father's connections and her achievements as a pilot) was appointed as civil defence commissioner in London with the Civil Air Guard. When war broke out, she recognised an opportunity to break gender barriers and was determined for women to be included in the ATA. Pauline personally lobbied the Ministry of Civil Aviation to allow women to work for the ATA, thus helping alleviate the pressure building on both the ATA and the RAF. Her efforts bore fruit when she was appointed to lead the women’s section of the ATA, and a month later she had the first eight female pilots trained and ready to ferry Tiger Moths from factories to the front lines.

Pauline Gower in a Tiger Moth

Unfortunately, the first female pilots were paid at a lower rate compared to their male counterparts. And simply would not do for Pauline. She was utterly determined, and unashamedly called in her father’s connections in the government to overturn the two-tier system. In 1943, they achieved pay parity with the male pilots - a first in the world of aviation.

JACKIE COCHRAN

Among the American women who joined the ATA in 1941 was Jackie Cochran. A skilled aviator, Jackie was one of the first women to ferry aircraft across the Atlantic. Her influence extended beyond her flying duties, as her leadership and advocacy were instrumental in the formation of the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) in the US, a programme inspired by the ATA’s success. WASP trained women to fly non-combat missions, allowing more American pilots to serve on the front lines.

Jackie Cochran was an American born in poverty who married a billionaire and became a millionaire in her own right by launching a highly successful make-up chain. Pictured with her Beech D17W Staggerwing.

MAUREEN DUNLOP

Born on the 26th of October, 1920, in Argentina to British parents, Maureen Dunlop’s fascination with aviation began at a young age. She was captivated by the idea of flying, and she pursued her passion relentlessly, earning her pilot's licence in her teens. In 1942, Maureen joined the ATA and her fearless attitude and exceptional flying abilities quickly set her apart. She flew a range of aircraft, from the Spitfire to the Wellington bomber, and was known to handle these powerful machines with precision and grace. One of the most iconic photos of an Attagirl was captured when Maureen stepped out of a Spitfire, looking composed and confident with her hair blowing in the wind - an image which captured the public’s imagination and symbolised the glamour and heroism of the ATA.

Maureen Dunlop became a poster girl for the ATA after a photo appeared on the cover of the Picture Post, 1944

MARY DE BUNSEN

Mary was born to a wealthy family on the 29th of September, 1910. Her father, Sir Maurice de Bunsen, was a distinguished diplomat. Despite her privileged background, Mary was drawn to the skies, eager to escape the balls she was expected to attend in higher society. While she failed in her first attempt to join the ATA, she tried again and successfully joined the ATA in 1941 and was stationed at the No. 15 all-women's ferry pool in Hamble, Hampshire. Despite running many successful missions, Mary was known for damaging the landing gears on Spitfires.

ROSEMARY REES

One of theFirst Eight, Rosemary joined the ATA on New Year's Day, 1940, after already accumulating over 600 hours in the air and had been flying since 1933. In September 1941, she accepted the role of deputy to Margaret Gore (an ATA commander) at the Hamble ferry pool, and by the end of the war was one of the only eleven women to have flown the 4-engine bombers. Overall, Rosemary piloted 91 different aircraft and was one of the few to receive an MBE for her time in the ATA.

ELEANOR WANDSWORTH

Eleanor began her journey with the ATA in 1943 as an architectural assistant, spurred by an advertisement seeking female pilots. With just 12 hours of training, she demonstrated her ability to pilot an aircraft and was one of the first six women to be accepted with practically no flying experience. After only 12 hours of training, Eleanor was proficient enough to fly her first aircraft. When interviewed, Eleanor said that her favourite aircraft to fly was the Spitfire: “It was a beautiful aircraft, great to handle and I was fortunate to be able to fly 132 of them during my time at the ATA.”

Eleanor Wandsworth

JOY & YVONNE

Joy Lofthouse and her sister Yvonne MacDonald (née Gough, with the sisters being known as the Gough girls) embarked on an extraordinary journey when they both responded to an advertisement inAeroplanemagazine, seeking recruits for the ATA’s ‘ab initio’ scheme in the summer of 1943. This initiative addressed the need for more pilots to serve in the ATA without prior flying experience. Among the 2,000 applicants, only 17 were selected for the intensive training programme. Remarkably, neither sister had flown an aircraft before and were both accepted on the programme.

Joy

Yvonne’s decision to join the ATA was particularly poignant, having recently lost her husband, Tom, an RAF pilot, in a bombing raid over Berlin. Despite this personal tragedy, she viewed joining the ATA as a deeply meaningful contribution to the war effort. Reflecting on her decision, Yvonne remarked “It wasn’t a death wish; I saw it as one of the most worthwhile jobs I could possibly have… Once I knew they would accept women without experience, it seemed natural to me to do my part for the war by flying.”

Yvonne

MARY ELLIS

Born in Oxfordshire, Mary Ellis developed a fascination with aviation from childhood, as her family home was near RAF bases in Bicester Airfield and Port Meadow. At the age of 16, she started taking flying lessons and was a trained pilot before the war. Inspired by a BBC radio advert, Mary joined the ATA in 1941. Mary was so exceptional at navigating her aircraft in poor weather conditions that she earned the nickname “Fog Flyer”. By the end of the war, Mary had delivered approximately 1,000 aircraft during her time stationed at the No. 15 Hamble pool.

Mary Ellis

MOLLY ROSE

Molly Rose had a strong aviation background and piloted 36 different types of aircraft for the ATA. However, her resilience was put to the test in the summer of 1944 when she received a telegram stating that her husband, Bernard, a tank commander, was missing and presumed dead. Despite this devastating news, Molly continued her flying duties, stating, "Sitting around, waiting for news, was no tonic for anyone." Remarkably, she later discovered that Bernard had survived; he had been captured and held in a POW camp. The couple was joyfully reunited at the end of the war.

Molly Rose, 1942

MARION WILBERFORCE

Inspired by her two brothers, Marion took up flying and earned her private pilot’s license in 1930. In 1937, using money she had earned as a child on the stock exchange, she purchased her first aircraft. For tax reasons, her planes were classified as farm implements and kept in a barn. These aircraft were used to transport poultry and Dexter cattle cows, which Marion bred specifically for their small size, allowing them to fit into her plane.

Pictured from left to right: Gabrielle Paterson, Rosemary Rees, Marion Wilberforce

On one occasion, she arrived at a factory to collect an aircraft, only to find the workers on strike, preventing its release. Undeterred, Marion went to the workers' canteen and delivered an impassioned speech about the war effort, convincing them to release the plane. She was also one of the select eleven women pilots who flew the Lancaster bomber, a notable achievement in her aviation career.

A modest individual, Marion consistently declined interviews about her wartime experiences and turned down an invitation to stand for Parliament. She also refused an MBE at the war's end. Marion continued to fly until the impressive age of eighty, maintaining her passion for aviation throughout her life.

TILLY SHILLING

Women played crucial roles in the Spitfire story, with some, like Beatrice 'Tilly' Shilling, making significant technical contributions. Working at the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough, the world's premier aeronautical research centre, Tilly faced a critical issue when the Battle of Britain began. It was discovered that the Rolls-Royce Merlin engines in Spitfires and Hurricanes would cut out during negative-gravity manoeuvres in dogfights. To address this, Tilly devised a quick and simple solution. She toured fighter bases with a team of fitters, drilling a hole in the carburettor float that allowed fuel to pass to the engine, preventing it from sticking during negative gravity. This ingenious fix was affectionately named "Miss Shilling’s Orifice" by fighter pilots and engineers.

Beatrice 'Tilly' Shilling, on her Norton racing motorcycle, 1930s

The role of the ATA was crucial to the RAF's success in World War II and, ultimately, the outcome of the war. As Lord Beaverbrook stated during the disbanding of the ATA on November 30, 1945, "Just as the Battle of Britain is the accomplishment of the RAF, likewise it can be declared that the ATA sustained and supported them in battle. They were soldiers fighting in the struggle just as completely as if they had been engaged on the battlefront."

The ATA women who piloted aircraft that defended the skies of Britain are unsung heroines of World War II. They performed an essential job that many men considered too difficult for them, proving their detractors wrong with immense courage, skill, and professionalism.

This is just a snapshot of a handful of women among the millions of Britons who were 'doing their bit' during those turbulent years. They worked on the Home Front in all sorts of less visible or glamorous jobs, demonstrating camaraderie and stoicism in ways that are unimaginable to us now.

Sources:

Peggy

July 27, 2025

Marion Wilberforce taught my brother to fly out of Leavens airfield very close to DeHavilland where my dad worked. She taught him every dog fighting trick in the book. I flew with him when at 18 he bought a Cornell trainer. I met Marion on several occasions. She had fiery red hair (which I assume was her own.) She told my brother of exploits but was a very unassuming person.