World War 2 marked a pivotal moment in global history, with nations engaged in devastating conflicts that reshaped political, social, and cultural landscapes. Within the tumultuous period, propaganda played a crucial role in shaping public opinion and mobilising support for various causes on both sides of the war, and one of the most subliminal but effective methods of propaganda was through women’s clothing. Join us as we explore the realm of Japanese propaganda clothing during World War II and its impact on wartime fashion.

For generations, clothing has served as a powerful medium for communicating identities, social standing, and loyalties. In times of conflict, its significance intensifies, offering a compelling avenue for showcasing patriotism, unity, and allegiance to one’s country. Governments throughout history have used fashion as a tool of propaganda, whether through uniforms that inspire fear in enemies or fostering public pride in national identity - the UK was no exception and our blog posts on ‘Beauty for Duty’ and ‘Utility Clothing’ look at how the British government weaponised fashion in WW2.

Women's kimono, "Airplanes and Clouds", 1930s. The obi (sash/belt) on the kimono has unusually strong military imagery for a woman's garment, featuring a battleship and a military marching song which are softened by the flowers and softer feminine colours.

Propaganda clothing in Japan was a means to promote nationalist fervour and ideological conformity. Traditional Japanese garments such as kimono and 'haori' were infused with patriotic imagery, transforming them into instruments of propaganda. The creation of propaganda kimonos is thanks to three pivotal factors: the late 19th-century introduction of Western textile production and equipment to Japan, the societal and political aspirations for Japan’s modernisation by the ruling powers, and the political motive to rally backing or colonial expansion, particularly following the 1931 invasion of Manchuria in China.

With the introduction of new textile manufacturing and successful export of various commodities, Japan experienced rapid economic growth that propelled it towards modernisation. Since the mid-19th century, the Japanese military had adopted European-style uniforms, and city-dwellers also embraced the more convenient and unrestrictive Western attire, but those living in rural Japan still favoured the kimono.

Known as 'omoshirogara' (interesting or novelty designs), newly printed textiles in the early 1920s and mid-1930s often showcased urban landscapes featuring subways, ocean liners, and steam locomotives. However, when Japan entered an alliance with Germany and Italy in 1940, these designs became more propaganda-focused. Kimonos tailored for boys and men frequently featured military motifs and scenes of political victories, aiming to instil a sense of pride and courage, ultimately encouraging enlistment in the armed forces.

Child's padded kimono, "Army Toys". Early 1930s, printed on silk lined with cotton and muslin.

By contrast, designs targeted at young girls adopted a more subtle approach, emphasising the splendour of Japanese culture through imagery such as cherry blossoms and the iconic Mount Fuji.

"Modernity", 1930. A design printed on muslin

Crafted to maintain fashionability while stirring patriotism, these designs mirrored the approach taken with other graphics and slogans used in Japanese media - similar to the imagery created for the home front campaign in the UK. Remarkably, the designs became popular with the Japanese public, requiring little coercion from the government to embrace them.

Despite their widespread appeal, these propaganda designs weren’t often worn in public, as the vibrant patterns and hues were traditionally associated with the upper classes of society. This practice stemmed from regulations governing textile attire dating back to the Tokugawa era (1621 - 1867). The laws outlined that only certain fabrics and colours could be worn by certain classes, with the most luxurious of these reserved for the higher classes. Propaganda prints on kimonos were predominantly flaunted by the privileged classes within the confines of their homes or at private gatherings as a statement of their position. However, these prints did trickle down to the lower classes, finding their way into garments like 'nagajuban' (worn under the kimono), though they remained largely concealed from public view.

Kimono lined with Axis flags and navy images, 1940-1941

Women's summer kimono from the 1930s.

The resource constraints faced by the Allies during the war were mirrored in Japan’s struggles. As early as 1939, cotton shortages prompted regulations in textile production. By 1941, magazines began featuring articles on repurposing existing clothing, similar to the ‘Make Do and Mend’ campaign in the UK. Soon after, clothing rationing was implemented on a coupon system. The allocation of coupons differed by location, with those who lived in larger cities receiving 100 annually and rural residents 80. For instance, a man's suit, trousers, or jacket required 50 coupons, while a shirt or blouse cost 12, and a hand towel only 3.

A postcard from 1945 featuring a young girl wearing a homemade kimono. The text reads "It is a kimono made of various homemade fabrics. Please mix and match plain and patterned fabrics with beautiful colours."

Credit: oldtokyo.com

In September 1943 Japanese Commerce and Industry Minister Nobusuke Kishi chastised Japanese women for owning twice as many dresses as their American counterparts, encouraging them to make do with their existing wardrobes to conserve textiles for the war effort. As supplies dwindled, the Japanese government tightened restrictions even more in 1944, halving the allocation of coupons per person.

Policeman warning women against wearing fancy clothing in public places. Osaka, Japan, August 1940.

Despite the constraints imposed on textiles and coupon restrictions, Japan remained resourceful with its wartime fashion for both men and women. Recognising the impracticality of kimonos posed as attire for ‘defending the country’, the Japanese government introducedkokuminfuku inNovember 1940 - a military-style uniform for men exclusively produced in khaki, the official colour of national defence. However, as men departed for military service, women assumed the roles left vacant and had to adjust their attire accordingly. Within months of the male civilian uniform, the Committee for Reform of National Dress was established to devise a comparable outfit for women.

The public was urged to participate in an open competition by submitting their design concepts for standardised clothing (with a heavy emphasis that the designs should be “appropriate in appearance for world leadership”), and the public eagerly engaged. This inclusive approach of seeking input from the public resonated well in Japan, perhaps highlighting a contrast with the British government’s approach in its ‘Utility Clothing’ scheme. Unlike Japan’s model, where public input was valued, the British public had no involvement in the initial designs created for the CC41 label. Despite the involvement of esteemed designers, the scheme faltered on its initial launch.

A postcard from 1945 featuring "active clothing". The text reads "This style is a crisp, active garment. It can be worn all year round by adjusting the blouse. It can be made from an old dress."

Credit: oldtokyo.com

The Japanese public selected 3 designs suitable for women’s standard attire:

- A western-style one or two-piece dress which was more functional than traditional Japanese kimono, but remained incredibly modest.

- An adapted kimono with a narrow skirt and tighter sleeves, ultimately saving more than 4 meters of fabric per kimono

-

Monpe, a jacket and trousers style. The trousers featured a loose waistband and a drawstring hem around each ankle.

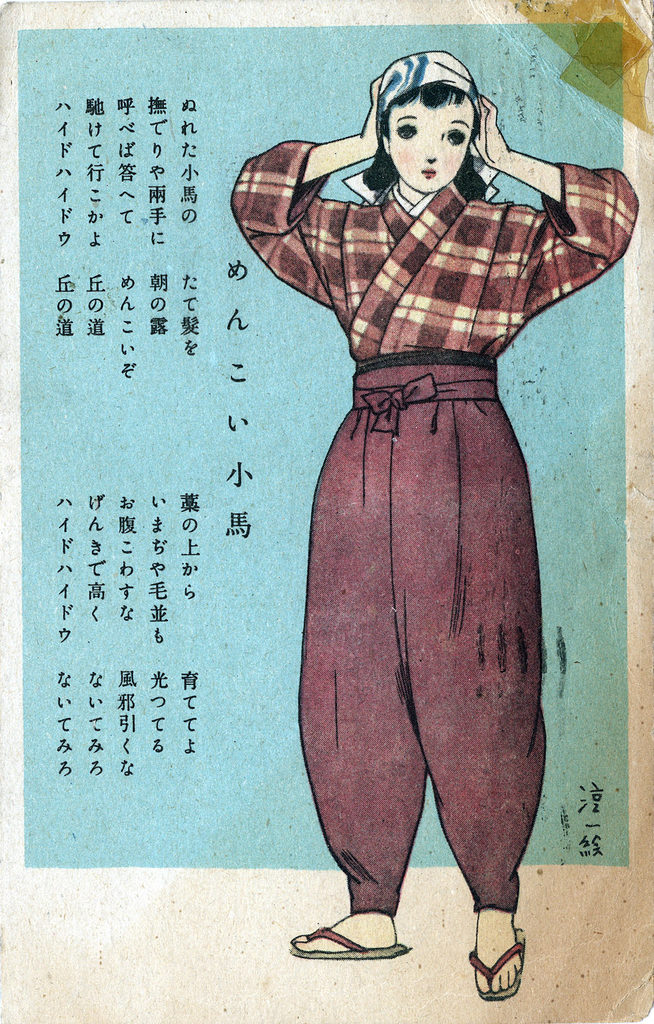

A postcard from 1940 featuring a young girl wearing monpe (plain, loose-fitting work trouser). Source: oldtokyo.com

Initially,monpe, one of the winning designs, was not perceived as particularly flattering or feminine in comparison to traditional kimono. However, its practicality swiftly overshadowed concerns about its femininity when air raids, starting with the first over Tokyo on the 18th of April 1941, became a reality. Monpe proved to be a quick and efficient garment to don over existing clothing during air raids, similar to the ‘siren suit’ popularised in the UK and soon became a staple of wartime fashion and a symbol of the Japanese home-front. Popular women’s magazines also provided instructions on repurposing old kimonos into monpe,while the Home Ministry sponsored workshops in schools, encouraging female students to sew their own garments.

Monpe. Mitsukoshi Department store catalogue, 1940.

Following the conclusion of the war, Japan swiftly prohibited the use of propaganda imagery, leading to a stigma associated with garments featuring such designs. They were regarded with disapproval and brought feelings of shame. It wasn’t until recent years kimono enthusiasts discovered propaganda kimonos, as they had been effectively concealed in Japan’s history.

Reflecting on the heritage of WW2 Japanese wartime fashion provides a valuable understanding of the intricate dynamics of wartime propaganda and the strategies employed by governments on both sides of a war to sway public sentiment. Japanese wartime fashion stands as a captivating convergence of fashion, politics, and ideology. From the enforcement of stringent dress regulations to the emergence of inventive designs, fashion not only mirrored societal norms but acted as a vehicle of resistance.

Old Tokyo, a website full of Japanese history

Jacar, a website featuring original Japanese media around wartime clothing

Koyuki Aker

October 08, 2025

I’m making some art about Japanese wartime textile patterns and this was a very informative read. Thank you!